Archiving the historic Embassy Theatre – Ft. Wayne, Indiana

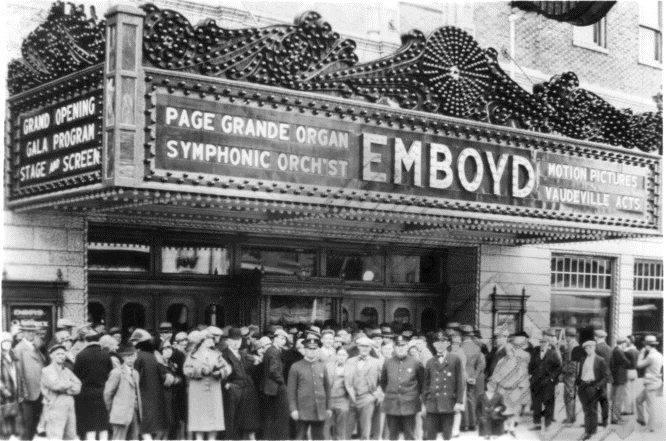

“Today at 1 P.M. Fort Wayne Proudly Receives Its Magnificent New Theater. Come to the opening today of the Emboyd. You’ll thrill to its sumptuous beauty—revel in its atmosphere of luxurious comfort—and marvel at the giant inaugural entertainment program. Follow the Eager Throngs to the Opening of Indiana’s Wonder Theater—a Gala Event the Memory of Which You’ll Cherish Forever!”

This exciting text appeared in the Fort Wayne News-Sentinel for 14 May 1928 in a large advertisement featuring a fanciful drawing of the theater’s interior and an enticing glimpse of the program of film (Richard Dix in Easy Come, Easy Go), vaudeville, and music provided by Wilbur Pickett’s Emboyd Concert Orchestra and Percy Robbins at the four-manual Grande Page organ.  This year, the theater, now known as the Embassy, is preparing to celebrate its ninetieth anniversary with a special show recreating the spectacle—if not the exact program—of the 1928 opening and the release of several new CDs on its original and famous Grande Page organ.

This year, the theater, now known as the Embassy, is preparing to celebrate its ninetieth anniversary with a special show recreating the spectacle—if not the exact program—of the 1928 opening and the release of several new CDs on its original and famous Grande Page organ.

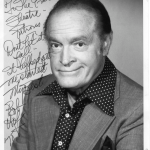

But it is also marking the occasion by new efforts to preserve and commemorate the theater’s history, especially its archive, which includes among many other things more than 600 photographs of performers who appeared at the theater and its sister, the Palace Theater, from the 1930s through the early 50s, ranging from some of the most famous bands and bandleaders to acrobats, animal acts, comedians, dancers, emcees, impressionists, instrumentalists, singers, ventriloquists, and so on. All the photographs were inscribed to the theater’s long-time stage manager, Bud Berger (left, above photo), and they provide a veritable Who Was Who of entertainers of the period, some still famous and others now largely forgotten.

Among the most famous would surely be Bob Hope, who served as Master of Ceremonies from 16 May to 8 June 1929 and returned on a number of later occasions, including a benefit performance on 30 September 1978 in support of the theater’s restoration. Dancers were very popular at the theaters, and two of the most famous, representing quite different traditions, performed in the 1930s. Eleanor Powell appeared at the Emboyd on 9–11 March in the 1933 edition of George White’s Scandals and later sent Berger an inscribed photograph commemorating her appearance in MGM’s Broadway Melody of 1936.

Powell’s demure appearance is certainly in contrast to Sally Rand who also appeared at either the Emboyd or Palace

Theater in the 1930s. Major Bowes’ Collegiate Revue of 1938 brought the six winners of the National Collegiate  Dance Championships to Fort Wayne, where

Dance Championships to Fort Wayne, where they performed the Shag Dance and gave Berger an elaborately inscribed photograph. And in the same year, Doris Dupont appeared with Count Berni Vici’s revue and inscribed her photograph: “To Bud: From the ‘rocky coast’ of Maine, to the ‘sunny shores’ of California – there ‘ain’t’ no better. Sincerely Doris Dupont.”

they performed the Shag Dance and gave Berger an elaborately inscribed photograph. And in the same year, Doris Dupont appeared with Count Berni Vici’s revue and inscribed her photograph: “To Bud: From the ‘rocky coast’ of Maine, to the ‘sunny shores’ of California – there ‘ain’t’ no better. Sincerely Doris Dupont.”

Comic dance acts were also very popular. Some of these spoofed the conventions of ballroom dancing, others involved acrobatics, and still others such as the Four Clymas and the  Appletons expanded on the tradition of Apache Dancing. Billboard

Appletons expanded on the tradition of Apache Dancing. Billboard (17 August 1940), p. 19, described the Four Clymas as “one of the most novel acts ever to play here [Hollywood].” In a Parisian underworld setting, the three males and a femme throw each other all over the place in a wild rough-and-tumble scramble of arms, legs, knives, and guns. Their stuff is strictly above the average. Joe Clymas and Loretta come on later to do a terp number in waltz time, a creditable performance.” The Four Clymas appeared at the Palace Theater in 1936, and one of their members, Charles Carman, returned to Fort Wayne in January 1943 in a new group, the Appletons. Billboard (24 November

(17 August 1940), p. 19, described the Four Clymas as “one of the most novel acts ever to play here [Hollywood].” In a Parisian underworld setting, the three males and a femme throw each other all over the place in a wild rough-and-tumble scramble of arms, legs, knives, and guns. Their stuff is strictly above the average. Joe Clymas and Loretta come on later to do a terp number in waltz time, a creditable performance.” The Four Clymas appeared at the Palace Theater in 1936, and one of their members, Charles Carman, returned to Fort Wayne in January 1943 in a new group, the Appletons. Billboard (24 November  1945), p. 38, describes their act as a “familiar rough-house Apache

1945), p. 38, describes their act as a “familiar rough-house Apache act, and it is plenty rough. Kicks, prop busting over each other’s heads, knife throwing, gun play and body tossing brings gasps from the mob….”

act, and it is plenty rough. Kicks, prop busting over each other’s heads, knife throwing, gun play and body tossing brings gasps from the mob….”

Music was always central to vaudeville, and the Emboyd and Palace Theaters hosted many of the popular bands of the day: Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, Les Brown, Henry Busse, Cab Calloway, Eddy Duchin, Duke Ellington, Ted Fio Rito, Jan Garber, Horace Heidt, Art Jarrett, Spike Jones, Art Kassel, Ted Lewis, Little Jack Little, Vincent Lopez, Benny Meroff, Frankie Masters, Russ Morgan, Red Norvo, George Olsen, Tony Pastor, Artie Shaw, Orrin Tucker, Ted Weems, Lawrence Welk, and many others. Every one of these left an inscribed photograph for Berger’s collection.

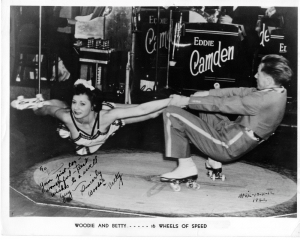

Of course, all these bands featured singers and frequently dancers, and they too left their own inscribed photographs,  including Bonnie Baker, Blair Sisters, Cholly and Dotty, Perry Como, Harry Cool, Doris Day, Bob Haymes, Marvel Marilyn Maxwell, Billy Sherman, Step Brothers, Larry Stuart, Elmo Tanner, Liz Tilton, Gene Williams, and many others. Some bands also featured full-scale revues that included comedians and novelty acts. Among the most unusual were Woodie and

including Bonnie Baker, Blair Sisters, Cholly and Dotty, Perry Como, Harry Cool, Doris Day, Bob Haymes, Marvel Marilyn Maxwell, Billy Sherman, Step Brothers, Larry Stuart, Elmo Tanner, Liz Tilton, Gene Williams, and many others. Some bands also featured full-scale revues that included comedians and novelty acts. Among the most unusual were Woodie and  Betty, an acrobatic roller-skating act that appeared with Eddie Camden’s orchestra and as a solo act in vaudeville, and Rita Devere, an acrobatic contortionist who appeared with Benny Meroff’s orchestra.

Betty, an acrobatic roller-skating act that appeared with Eddie Camden’s orchestra and as a solo act in vaudeville, and Rita Devere, an acrobatic contortionist who appeared with Benny Meroff’s orchestra.

Comedians and comic ensembles were staples of the vaudeville circuit and, like Bob Hope, sometimes doubled as Masters of Ceremonies. Bob Hope was not the only famous example to appear in this capacity twice at the Emboyd: Will Mahoney appeared in 1929 in an act billed as “Why Be Serious featuring Will Mahoney” and again in 1952, billed as “One of the World’s Greatest Entertainers featuring Will Mahoney, comedy” (on this occasion, he inscribed his photograph: “To Bud. Yours to the last ‘Curtain,’ Will Mahoney, Jan 25th 1952.”). Many of the comedians who appeared are barely remembered today, but in their day, they were immensely popular  and widely reviewed in Variety and Billboard. The Arnaut Brothers, for example, were famous for their bird romance in an invented bird language and with head and tail feathers (unfortunately, the bottom of this picture was damaged over the years). Other examples might include Hap Hazard and Mary Hart, husband-and-wife comedians whose act was billed as “Hap Hazard, the Careless Comedian, and Mary Hart, Who Cares Less”; Jackie Jay, a comedian with Fred Waring and His Pennsylvanians; and Jack E. Leonard, an insult comedian whose act anticipated Don Rickles.

and widely reviewed in Variety and Billboard. The Arnaut Brothers, for example, were famous for their bird romance in an invented bird language and with head and tail feathers (unfortunately, the bottom of this picture was damaged over the years). Other examples might include Hap Hazard and Mary Hart, husband-and-wife comedians whose act was billed as “Hap Hazard, the Careless Comedian, and Mary Hart, Who Cares Less”; Jackie Jay, a comedian with Fred Waring and His Pennsylvanians; and Jack E. Leonard, an insult comedian whose act anticipated Don Rickles.

Magicians, puppeteers, and ventriloquists capitalized on the aura of fantasy created by the movie palace, and many of them played at the Emboyd and Palace. Harry Blackstone, “The World’s Greatest Magician,” appeared in 1941; Jack Gwynne, who specialized in performing astonishing feats while completely surrounded by an audience, brought his show to the theaters in 1942; Dante’s revue Sim Sala Bim played in 1944; and Ade Duval, famous for his “Rhapsody in Silk,” followed in 1952. Probably the most famous  ventriloquists and puppeteers to appear were Paul Winchell with his dummy Jerry Mahoney and Frank Paris, the creator of Howdy Doody, but audiences of the day also applauded the LeRoy Brothers with Jimmy Durante “da marionette” and Bob Neller, whose dummy “Reggie” created remarkable effects with twelve different movements of the upper and lower lips and mouth, nose, eyes, eyebrows, hands, and feet. Lester Oman’s marionettes even operated their own marionettes. Variety (3 December 1941), p. 27, described his act: “He differs from usual presentation of puppets, being shown in the spotlight full length pulling the strings, with the spot narrowing down entirely to the marionettes as he starts manipulating the colored jitterbug stepper. Skeleton dance, with the elongated skeleton covered with phosphorescent paint, is a trim novelty as the different limbs appear to come apart while dancing. Little old lady doll gives a change of pace. Finale is a girl drum major, a bit stilted, but mops up when the puppet starts twirling her baton.”

ventriloquists and puppeteers to appear were Paul Winchell with his dummy Jerry Mahoney and Frank Paris, the creator of Howdy Doody, but audiences of the day also applauded the LeRoy Brothers with Jimmy Durante “da marionette” and Bob Neller, whose dummy “Reggie” created remarkable effects with twelve different movements of the upper and lower lips and mouth, nose, eyes, eyebrows, hands, and feet. Lester Oman’s marionettes even operated their own marionettes. Variety (3 December 1941), p. 27, described his act: “He differs from usual presentation of puppets, being shown in the spotlight full length pulling the strings, with the spot narrowing down entirely to the marionettes as he starts manipulating the colored jitterbug stepper. Skeleton dance, with the elongated skeleton covered with phosphorescent paint, is a trim novelty as the different limbs appear to come apart while dancing. Little old lady doll gives a change of pace. Finale is a girl drum major, a bit stilted, but mops up when the puppet starts twirling her baton.”

Animal acts at the Emboyd included birds, dogs, bears, and even a seal! Bill Hughes, a ventriloquist, and Blackie  appeared at the Emboyd billed as “World’s Most Educated Crow,” with the crow and Hughes engaging in comic dialogue. Ed Ford and Whitey, billed at the mboyd

appeared at the Emboyd billed as “World’s Most Educated Crow,” with the crow and Hughes engaging in comic dialogue. Ed Ford and Whitey, billed at the mboyd  as “Dog Gone Crazy,” were a dog comedy act, with Whitey dressed in top hat and tails playing an inebriated gentleman. Max and His Gang was an act described by Billboard (30 January 1943), p. 16, as taking in “two acrobatically-inclined pooches. However, Max is one dog fancier who doesn’t take the bows for his mutts. Earns plenty of them himself with a variety of stunts that includes an acro soft-shoe routine, hoop-whirling proficiency, and a complete body bend to turn his head around and back to pick up the floored hankie.” Trained

as “Dog Gone Crazy,” were a dog comedy act, with Whitey dressed in top hat and tails playing an inebriated gentleman. Max and His Gang was an act described by Billboard (30 January 1943), p. 16, as taking in “two acrobatically-inclined pooches. However, Max is one dog fancier who doesn’t take the bows for his mutts. Earns plenty of them himself with a variety of stunts that includes an acro soft-shoe routine, hoop-whirling proficiency, and a complete body bend to turn his head around and back to pick up the floored hankie.” Trained  bears appeared riding scooters and a motorcycle in 1943, but Sharkey the Seal eclipsed them with his appearance at the Emboyd on 8–9 December 1951, billed as “The Seal with the Human Mind,” in which he juggled, played cards, did tricks, and applauded himself.

bears appeared riding scooters and a motorcycle in 1943, but Sharkey the Seal eclipsed them with his appearance at the Emboyd on 8–9 December 1951, billed as “The Seal with the Human Mind,” in which he juggled, played cards, did tricks, and applauded himself.

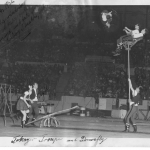

Finally, acrobatic routines were popular, whether as part of singing-and-dancing ensembles or as pure acrobatic acts involving teeter-boards, roller skates, swings, tight-rope walking, unicycles, or incredible feats of balance. The most famous of the singing-dancing-acrobatic ensembles to appear in the collection of photographs is the O’Connor family, known as “The Royal Family of Vaudeville.” Donald O’Connor, who went on to become a star on stage and in film and television, appears in front, second from the left (Berger’s hand has added names to five of the six individuals, clockwise from top left: Bill, Jack, Nellie, Pat, and Don; the person on the far left is Effie, the matriarch).

Other purely acrobatic performers appearing at the Emboyd and Palace include Frank and Dolorez Evers (tight-rope walkers); The Great Yacopis, The Langs, The Mar-Vels, and the Tokayer Troupe (teeter-board acrobats); and the Orantos and Walkmir (pole balancers).

Some of their acts were exceedingly complicated and dangerous. Variety (3 August 1938), p. 46, described the Yacopis as doing “all the teeter-board stunts done by other troupes and add several hair-raisers of their own. Windup stunt is a complete double-up of the familiar one of the man jumping onto a teeter to back-flip his partner into a chair held on the shoulders of a third. As done by the Yacopis, they’re standing four-high at the finish.” Walkmir appeared in 1942 with an act in which he balanced a pole on his forehead [!] supporting as many as five people at a time, each of them performing some acrobatic feat of their own. The Langs’ act, billed at the Emboyd as “Thrill-A-Batricks,” was described by Billboard (18 June 1949), p. 45: “a sensational sight act. It’s a good, clean looking act with lots of class. Using two teeterboards, a perch chair and a high platform, the troupe went thru a routine that had them on edge. The stuff was deliberately built up for added suspense, including several studied fluffs, and won tremendous hands.” Acrobats

jumping onto a teeter to back-flip his partner into a chair held on the shoulders of a third. As done by the Yacopis, they’re standing four-high at the finish.” Walkmir appeared in 1942 with an act in which he balanced a pole on his forehead [!] supporting as many as five people at a time, each of them performing some acrobatic feat of their own. The Langs’ act, billed at the Emboyd as “Thrill-A-Batricks,” was described by Billboard (18 June 1949), p. 45: “a sensational sight act. It’s a good, clean looking act with lots of class. Using two teeterboards, a perch chair and a high platform, the troupe went thru a routine that had them on edge. The stuff was deliberately built up for added suspense, including several studied fluffs, and won tremendous hands.” Acrobats  were still popular in the 1950s when both the Orantos and the Tokayer Troupe appeared at the Emboyd. Like Walkmir, the Orantos, billed at the Emboyd on 26–27 January 1952 as “European High Perch Experts,” balanced the pole on which other acrobats performed amazing feats For their part, the Tokayer Troupe, billed at the Emboyd on 29 March 1952 as “Perilous Acro, Difficult Unequaled Sensation,” specialized in catapulting members of the troupe from a teeter-board through the air to land on a chair held aloft on a pole.

were still popular in the 1950s when both the Orantos and the Tokayer Troupe appeared at the Emboyd. Like Walkmir, the Orantos, billed at the Emboyd on 26–27 January 1952 as “European High Perch Experts,” balanced the pole on which other acrobats performed amazing feats For their part, the Tokayer Troupe, billed at the Emboyd on 29 March 1952 as “Perilous Acro, Difficult Unequaled Sensation,” specialized in catapulting members of the troupe from a teeter-board through the air to land on a chair held aloft on a pole.

* * * * * * * * *

The database for cataloguing the pictures had to take into account all the categories of material contained in the archive, such as audio-visual material, correspondence, documents, negatives, newspaper items, photographs (signed, unsigned, inscribed to Bud Berger), Playbill, Poster, Program, Scrapbook, Stool (the archive includes stage stools signed by various performers), and Other. Each record includes the following fields: Archive index number, Object (i.e., the category of material, in this case “photograph, inscribed to Bud Berger”; the other categories are selected from a drop-down menu to insure consistency), Name(s), if any or a description of the object; Date(s) if any; Dimensions and pagination as applicable; Description; and Picture.

Within this design, the creation of each photograph’s record began with measuring the photograph and deciphering the inscription, which sometimes also provided the date or dates on which the act appeared at the Emboyd or Palace. This was not always easy to do because in some cases all that was left was the impression of the pen on the photograph, and these inscriptions had to be transcribed with raking light. An additional challenge was sometimes presented by the handwriting itself, which  could be clear and legible or difficult to decipher, especially the signatures. Finally, not all the inscriptions are in English: some are in Dutch, Danish, Swedish, French, and Hawaiian. But with the aid of internet searches of newspapers and trade journals, it was eventually possible to transcribe all of

could be clear and legible or difficult to decipher, especially the signatures. Finally, not all the inscriptions are in English: some are in Dutch, Danish, Swedish, French, and Hawaiian. But with the aid of internet searches of newspapers and trade journals, it was eventually possible to transcribe all of  them and provide some identification of the performers beyond their names. All of this was included in the Description field of the record for each photograph. The sample shows records for index numbers 567 (The Tokayer Troupe) and 568 (Sonny Skyler).

them and provide some identification of the performers beyond their names. All of this was included in the Description field of the record for each photograph. The sample shows records for index numbers 567 (The Tokayer Troupe) and 568 (Sonny Skyler).

A removable label with the archive index number was affixed to the back of each picture as it was catalogued. When the catalogue was complete, each picture was placed in a polyethylene envelope, which was in turn placed in an acid-free, lignin-free buffered envelope, the catalogue record was attached to the outside of the envelope, and the envelopes were placed in archival print boxes.

Cataloguing of the archive continues and the full catalogue will eventually be posted on the Embassy Theater’s website. An excerpt covering the 600+ Berger-inscribed photographs will soon be available on the website so that theater and vaudeville historians and afficionados may easily consult it. In the meantime, the two catalogues of the Embassy’s collection of more than 4000 slides for its Brenograph, including images of every slide, are already available for online viewing or downloading at <http://fwembassytheatre.org/about-us/historic-brenograph/>.

If you find this story fascinating, we have a treasure trove of information about the history of your favorite theatres. Sign up for an account on historictheatres.org and enter through the STAGE DOOR!

For nearly fifty years Theatre Historical Society of America has been celebrating, documenting, and promoting the architectural, cultural, and social relevance of America’s historic theaters. However, we can’t do it alone. Support from cinema lovers, architects, historians and people like you are paramount to our success. Become a member today, and help us preserve the rich history of America’s greatest theatres.